Eden: More Than Just A Garden

By Ella Heckman, C2ST Intern, Loyola University

In the digital age, it can be easy to forget that we as humans need to be in touch with nature and the world around us. The demands of our busy, everyday lives can make it hard to prioritize our health and get outside for a walk, let alone to do it for our mental health. In urban environments, research is increasingly showing that there is a strong connection between access to green spaces and improved mental health outcomes. Green spaces refer to anywhere dedicated to foliage, grass, plants, and nature for recreation or aesthetic purposes. These can be parks, pathways, gardens, and fountains in urban areas. Green spaces can provide a variety of psychological, emotional, and mental health benefits to the communities they are located in. Thus, it is important that as our society develops and our communities grow, we prioritize designing green spaces that nurture not only our bodies but also our minds.

Why does green space matter?

For our minds, access to green space can reduce our levels of stress and improve our quality of life. One study shows that proximity to green space has a positive effect on both people’s perceived mental health and their perception of their general health. Other research shows that green spaces have a positive effect on blood pressure, heart rate, and concentration, physiological responses that help us moderate stress and mental fatigue. We are better able to be present in natural settings than in built environments, enabling us to get rest, move through negative emotions, and self regulate. For our bodies, green spaces are places to play sports, to run and walk, and engage in recreation. Urban green spaces also improve community health and resilience, not just that of individuals. They are places for people to come together and build stronger community ties. Green spaces are also useful in mitigating climate change. Heavy rain events, rising temperatures, and worsening air quality are all among the symptoms of climate change felt by urban communities. Green spaces are naturally able to help absorb excess rainwater, filter and clean ambient air, as well as lower temperatures.

“Marymoor Park community garden” by King County Parks Your Big Backyard, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

What does it mean for a community to be healthy?

According to When Work Disappears by William Julius Wilson, a healthy community is defined by the following three principles.

- Social networks that are diverse, strong, and interdependent

- A strong sense of both collective and personal responsibility in addressing neighborhood problems

- A relatively high rate of participation in both voluntary and formal organizations

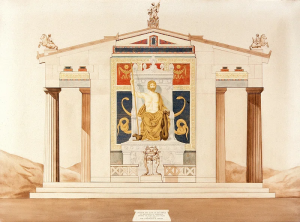

It is important that a green, community space reflects these principles, as well, in order to successfully provide a safe space for growth and healing. Additionally, elements of spiritual and emotional connection, healing, and contemplation in the built environment have long been considered important in medical settings. For example, the ancient city of Epidaurus was a city of healing that was designed in all ways to provide avenues for improving one’s health. The city’s design features views of nature, the incorporation of sunlight, spaces for theater and sports, and places of worship and commemoration. More than just grass and trees, green community spaces are opportunities for people to meet their neighbors, build relationships, and to spend quality time in nature reflecting on and processing the world around them.

(The temple of Aesculapius at Epidaurus via rawpiel)

Quantity and quality of these spaces are important, but equally as important is locating them in communities that need them the most. These are communities that bear the stresses of violence, discrimination, and hardship. One way of measuring this in Chicago is by measuring the amount of space that is covered by tree leaves and branches. The Morton Arboretum’s Tree Census conducted in 2020 has produced data on this topic, measuring green space in Chicago as the Urban Tree Canopy (UTC). According to an article by The Daily Northwestern, the overall average for Chicago’s UTC is 19%, but many neighborhoods on the South and West sides of Chicago have coverage of 15% or less. Historically, neighborhoods in these areas of Chicago have been subject to discriminatory housing practices that have made them less of a priority for development and investment in infrastructure, which includes green spaces. Thus, communities on the West and South sides of Chicago stand to gain a lot from incorporating health and community design principles into new parks, pathways, and gardens.

Urban green spaces exist at an important intersection of environmental justice, health, and community investment. Their benefits go beyond the individual benefits to people’s mental and physical wellbeing. Green spaces contribute to creating more resilient, sustainable, and connected communities. When we build and grow these spaces with their multiple functions in mind, we are better able to design a future for ourselves that is healthy and inclusive to all.

References

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5663018/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953610000675?via%3Dihub

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0142639042000324758

- https://www.epa.gov/green-infrastructure/social-benefits-green-infrastructure#fn1

- https://www.epa.gov/green-infrastructure/environmental-benefits-green-infrastructure

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/2152085

- https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/classics/intranets/students/modules/greekreligion/database/clumcc/

- https://apm.amegroups.org/article/view/15559/15655

- https://mortonarb.org/science/tree-census/#overview

- https://dailynorthwestern.com/2025/01/27/features/disparities-remain-in-access-to-green-spaces-between-chicagos-north-and-south-sides/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0169204618304316?via%3Dihub